The City of Tempe installed a bike box on the east side of 10th Street at Mill Ave. Note that in that google street view, there is already a bike box on the west side of the same intersection, installed by ASU according to the news item (apparently ASU and not the City of Tempe has jurisdiction over that piece of 10th street?). Continue reading “City of Tempe tests ‘Bike Box’”

The City of Tempe installed a bike box on the east side of 10th Street at Mill Ave. Note that in that google street view, there is already a bike box on the west side of the same intersection, installed by ASU according to the news item (apparently ASU and not the City of Tempe has jurisdiction over that piece of 10th street?). Continue reading “City of Tempe tests ‘Bike Box’”

Tag: infrastructure

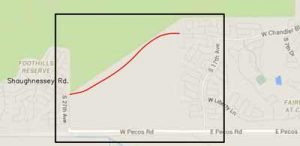

Chandler Boulevard Extension

When the final portion of the Loop 202 / South Mountain Freeway (SMF), the part that connects I-10 to Laveen, gets constructed it will replace Pecos Road. Pecos Road in Ahwatukee will be no more. This would otherwise leave everything west of 19th Avenue inaccessible from the rest of Ahwautkee, except for the freeway. The construction of SMF is supposed to begin summer 2016 and opens late 2019. Continue reading “Chandler Boulevard Extension”

When the final portion of the Loop 202 / South Mountain Freeway (SMF), the part that connects I-10 to Laveen, gets constructed it will replace Pecos Road. Pecos Road in Ahwatukee will be no more. This would otherwise leave everything west of 19th Avenue inaccessible from the rest of Ahwautkee, except for the freeway. The construction of SMF is supposed to begin summer 2016 and opens late 2019. Continue reading “Chandler Boulevard Extension”

Guadalupe and I-10 Bridge

For background on the SLM (Shared Lane Markings, a.k.a. sharrows) on the phoenix-side, see here, and more pictures here. That first link has an explanation as to why this bridge is an important and useful link for bicyclists. Continue reading “Guadalupe and I-10 Bridge”

Bicyclist killed in crash on Tucson’s northside

Read the deets on bicycletucson.com

1/24/2016 11:45am Tucson-area (Pima County Sheriff’s dept investigates).

A (somewhat elderly, coincidentally) female bicyclist traveling west on Sunrise Drive was killed by a very elderly motorist who was merging from Skyline Drive and apparently failed to yield. The bicyclists was later identified as 69 y.o. Patricia Lyon-Surrey. Continue reading “Bicyclist killed in crash on Tucson’s northside”

Funding proposal would add BLs on Chandler Blvd over I-10

This is pretty interesting for those of us in the Ahwatukee / Chandler area…

[ update: 11/2017 here is the “15%” Initial Project Assessment ; also see below for related update on Phoenix side circa 2020 ]

[Updates, as of early 2022; project is completed, scroll down]

City of Chandler has made a request for TA/CMAQ (see also alameda-drive-tempe-bicycle-pedestrian-proposal for more about TA/CMAQ) funding to add BLs on Chandler blvd between where they stop now (~ 54th St) and continue them to the “far” side of the bridge (City of Phoenix jurisdiction). It’s about .4 miles and the bottom line cost estimate is ~ 600,000 (details are in the link below). The main money driver here is some of the area needs to have curb/gutter/sidewalk relocated in order to make room. See the area on Google Maps. Continue reading “Funding proposal would add BLs on Chandler Blvd over I-10”

“Shoehorn” Bike Lanes

Attention bicyclist advocates: resist the urge to desire dedicated bicycling facilities when they won’t fit safely.

In the accurately scaled example diagram below (visit iamtraffic.org to tweak the dimensions and vehicle choices. A very cool tool!) a cyclist riding an upright bike is riding centered in a 5′ BL w/curb abreast of a Ford F-150 driving centered in the right general purpose travel lane (and DON’T say “car lane”, or somesuch).

McClintock Road resurfacing and left buffered bike lanes

[Mid-2018 southbound btw Southern and Baseline was restriped to add a 3rd southbound travel lane #restripe ]

[ONGOING still March 2017: There is a City of Tempe McClintock Project Page which is updated has has a long history section]

McClintock Drive resurfacing project, city of Tempe, AZ completed July 2015 — added left buffered Bike Lanes (LBBL) between Guadalupe and Broadway Roads, (the southbound side actually begins 1/2 mile north of Broadway at Apache) which incidentally crosses a major freeway interchange, US60. This is another in a series of “innovative” bicycle infrastructure projects recently completed in the City of Tempe. Continue reading “McClintock Road resurfacing and left buffered bike lanes”

City Cycling

My notations from the book: City Cycling edited by John Pucher and Ralph Buehler.

John Pucher is arguably the foremost American proponent of separate bicycling infrastructure; often called “Dutch-style”. He is an academic (planner-type; he’s not a traffic engineer) who has many published articles on the subject. And while he is a vociferous advocate for infra, if you read his work fully, he does at least mention there are other factors at play; and furthermore he considers these other factors as necessary to achieve high levels of safety and mode share a la Netherlands or Copenhagen. Among those other factors are, for example, the extremely high costs associated with motoring in those places with high bicycling mode share (duh). In the book, he covers these in the chapter Promoting Cycling for Daily Travel (see below). Here’s a brief excerpt where Pucher explains:

In short, such pro-bike ‘carrot’ policies [e.g. cycle tracks, bike parking] are indeed possible even in a car oriented country like the USA. By comparison, there is almost no political support in the USA for adopting and implementing the sorts of car-restrictive ‘stick’ policies listed in Table 3 [e.g. expensive fuel, high taxes, expensive vehicle parking, restrictive land-use policies] that indirectly encourage cycling in the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany.

Chapter: International Overview

Pucher has the same or similar table comparing fatalities/injuries for NL, DK, GER, UK, USA (fig 2.6); i’m sort of confused by the injury rate calculations as I explained here in reference to another Pucher paper Making Cycling Irresistible: Lessons from The Netherlands, Denmark and Germany that was citing the same or similar data.

Pucher has the same or similar table comparing fatalities/injuries for NL, DK, GER, UK, USA (fig 2.6); i’m sort of confused by the injury rate calculations as I explained here in reference to another Pucher paper Making Cycling Irresistible: Lessons from The Netherlands, Denmark and Germany that was citing the same or similar data.

He also shows trends for a bunch of countries in fig 2.7 — it would be worth it to put that into Evan’s perspective of looking at the broader traffic safety picture internationally: Traffic fatality reductions: United States compared with 25 other countries in which Evans shows how badly the US is lagging in overall traffic safety compared to virtually the entire rest of the developed world. Continue reading “City Cycling”

Warner and Kyrene

[updates, see warner-resurfacing for changes made in late 2016]

This article is to document the problems with the designated bike lane on Warner Road specifically at the intersection with Kyrene in the City of Tempe. Remember, there’s literally no excuse for bad bike lanes; if you can’t build them properly, then don’t build them. Continue reading “Warner and Kyrene”

Arizona does NOT have a mandatory Bike Lane Law

[this will be a catch-all for issues relating to legal requirement to use bike lanes (BLs). This was moved from the article explaining When must I ride my bicycle on the shoulder?, because it was muddying that issue unnecessarily; after all BLs are not shoulders and shoulders are not BLs. For all the details about shoulders, see that article; the short answer is their use is almost never required, that conclusion stems from the fact that shoulders are not part of the roadway.] Continue reading “Arizona does NOT have a mandatory Bike Lane Law”

One Road, 4 Treatments

Below for illustration is 4 different lane treatments commonly used on urban arterial roads — these all just so happen to be the same road, Chandler Blvd, in the City of Phoenix: Continue reading “One Road, 4 Treatments”

No Excuse

There is no excuse for improperly engineered bike infrastructure. It takes on two forms, 1) simple straight-up wrong, and 2) “fake” facilities, those which masquerade as something they’re not; they’re in reality nothing more than shoulders, yet they are intentionally tarted-up to appear to be, and even be referred to as bike lanes (see e.g. Flagstaff, below). Continue reading “No Excuse”

Should Warner Road bike lane have a “Combined” Turn Lane?

it is a common occurrence — familiar to every bicyclist — where you can be riding along a perfectly nice bike lane only to have it disappear for various reasons.

Bike lanes are highly prized for making cycling “more comfortable”; so I think it’s safe to say disappearing bike lanes would be considered quite stressful, and an impediment to cycling for many cyclists.

I have, over the past year, had occasion to regularly ride along Warner Road in Tempe (this area is sometimes referred to as “south” Tempe. Here’s a map of the general vicinity) between I-10 (the city limit) and McClintock Drive; it’s about 3.5 miles. The road is very much an arterial road with two fast through lanes (45mph, if i recall correctly) plus a bike lane each way plus some sort of middle lane throughout (it’s usually a TWLTL; two way left turn lane; it becomes a left turn lane at major intersections). The difficulty is at every intersection where there is a right turn only lane, the bike lane is dropped ~ 250′ from the intersection. This dropping occurs asymmetrically at some, but not all, of the major intersections. It is most prominent westbound: the lane drops at McClintock, Rural, Kyrene, Hardy, and Priest Drive. That is FIVE TIMES in three miles! Continue reading “Should Warner Road bike lane have a “Combined” Turn Lane?”

Cycle Tracks are NINE TIMES safer than roads?

There was a glowing article in theatlanticcities.com with the tantalyzying headline Dedicated Bike Lanes Can Cut Cycling Injuries in Half, referring to this study, published in a peer-reviewed, albeit public health and not a transportation, journal:

Route Infrastructure and the Risk of Injuries to Bicyclists: A Case-Crossover Study Kay Teschke, PhD et al. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:2336–2343. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300762 [pdf]

The design of the study is intriguing: it’s based on randomly choosing a “control site” along the participant’s (i.e. the crash victim) route.

Cycle Tracks are NINE TIMES safer?

Undoubtedly, the incredibly safety differential of “cycle tracks” will be the main take-away. The study found them to be NINE TIMES safer compared to their reference street (essentially a “worst case”: a mulitlaned arterial with on-street parking and no bicycle facilities whatsoever). The actual result is OR 0.11 (0.02, 0.54) — that is to say Odds Ratio of about 9 times safer, compared to the reference road.

Ok, so I don’t understand a lot about statistics, but the wide range between the lower and upper confidence interval (27X) is a clue. In short there is not very much/many cycle tracks in the study, mentioned only as “despite their (cycle track’s) low prevalence in Toronto and Vancouver”. There were two reported collisions, and 10 control sites on cycle tracks (out of N=648). In the critique of the study by John Forester he found during the study period there was apparently only one cycle track, the Burrard Street bridge, in both cities — my that is a “low prevalence” — here is his take-away:

In the much more impressive cycle-track issue, the authors proclaimed enormous crash reduction without informing the readers of the two relevant facts. First, that their data came from only one installation. Second, that that installation was not along a typical city street but in the only situation in which a plain cycle track could possibly be safe, a place without crossing or turning movements by motorists, cyclists, or pedestrians…

And even regarding the Burrard Street Bridge cycle-track, the timeline seems to conflict/overlap somewhat with the study dates. According to a surprisingly detailed account on wiki a test of what sounds to be the cycle-track was “to begin in June 2009. The proposed trial began on July 13. It saw the southbound motor-vehicle curb lane and the northbound-side sidewalk allocated to bicycles, with the southbound-side sidewalk allocated to pedestrians. The reassigned lane was separated from motor vehicles by a physical barrier” The timeline of the study was for bicyclist injuries presenting to the ERs “between May 18, 2008 and November 30, 2009″.

But wait? According to this (from mid-2011, i think, the date is unclear), Tesche said there are other cycle tracks: “However, we were able to examine separated bike lanes elsewhere in the city, including Burrard Bridge, Carrall Street, and other locations that met our definition: that is, a paved path alongside city streets that’s separated from traffic by a physical barrier,” Teschke told councillors.

Some Other Things i Noticed

The highest median observed motor vehicle speed along major roads was 44kph (27mph)! This is comically low compared to what I am used to here in Phoenix. Interesting trivia answer: 27.79mph — the fastest time on record for a person running.

One-third of the incidents involved collisions with MVs. The balance were various types of falls or collisions with objects. The one-third number is pretty close to the 26% reported by another ER-based survey of bicyclist injuries ( Injuries to Pedestrians and Bicyclists: An Analysis Based on Hospital Emergency Department Data. linked here ); though this isn’t directly comparable, e.g. in the former case, mountain biking was not eligible for the the study, whereas in the latter it was any sort of injury incurred on a bike.

There was a bunch of interesting data collected in the survey (which the author’s are nice enough to give a link to) that are not in the final study. I’m not sure why. I would have been interested to see various spins on lightness/darkness vs. cyclist’s light usage.

The Injury Prevention Article

and here’s another similar article, or perhaps pretty much the same(?):

Comparing the effects of infrastructure on bicycling injury at intersections and non-intersections using a case–crossover design Inj Prev doi:10.1136/ip.2010.028696 M Anne Harris, Conor C O Reynolds, Meghan Winters, Peter A Cripton, Hui Shen, Mary L Chipman, Michael D Cusimano. Shelina Babul, Jeffrey R Brubacher, Steven M Friedman, Garth Hunte, Melody Monro, Lee Vernich, Kay Teschke

NYC Protected Bike Lanes on 8th and 9th Avenue in Manhatten

According to a report (it’s really a brochure) by NYC DOT cited by americabikes.org; these are the “First protected bicycle lane in the US: 8th and 9th Avenues (Manhattan)”…”35% decrease in injuries to all street users (8th Ave) 58% decrease in injuries to all street users (9th Ave) Up to 49% increase in retail sales (Locally-based businesses on 9th Ave from 23rd to 31st Sts., compared to 3% borough-wide)”. I don’t know if or what the data are to back up these claims. I also don’t know much about how these are structured, what was done with signals, how long these are, or how long they have been in place… here is a google street view at 9th/23rd. (these segments show up in Lusk’s May 2013 AJPH article, discussed below)

Study of Montreal Cycle Tracks

Likewise, Harvard researcher Anne Lusk, et. al (includes Peter Furth, Walter Willett among others) has claims of safety increases Risk of injury for bicycling on cycle tracks versus in the street, brief report Injury Prevention. Streetsblog.org is expectedly uncritical, but a through rebuttal by mathemetician M Kary can be found hosted on John Allen’s site(older, 2012), and more recently (Jan2014) including links to Kary’s two original unedited letters, as well as the published commentary in Inj Prev. , which includes a rebuttal from the authors. There is some other rebuttal from Ian Cooper, in a comment below.

Methodology aside, though the study claims an increase in safety, it found only a modest increase: “RR [relative risk] of injury on cycle tracks was 0.72 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.85) compared with bicycling in reference streets”. I.e. a 28% reduction in crashes.

They had an interesting reference to Wachtel and Lewiston 1994, a much-cited sidewalk study.

More Lusk, July 2013 Article in AJPH

Oh, it’s like it never ends:

Bicycle Guidelines and Crash Rates on Cycle Tracks in the United States

Anne C. Lusk, PhD, Patrick Morency, MD, PhD, Luis F. Miranda-Moreno, PhD, Walter C. Willett, MD, DrPH, and Jack T. Dennerlein, PhD Published online ahead of print May 16, 2013; it was in the July printed edition of American Journal of Public Health. “For the 19 US cycle tracks we examined, the overall crash rate was 2.3 … per 1 million bicycle kilometers… Our results show that the risk of bicycle–vehicle crashes is lower on US cycle tracks than published crashes rates on roadways”. What are published rates? Later they say “published crash rates per million bicycle kilometers range

from 3.75 to 54 in the United States”. The first number is footnoted to Pucher/Irresistible (which is discussed and linked here), and the second to, if you can believe it, a study of Boston bicycle messengers (Dennerlein, 2002. I haven’t bothered to look that one up). In Pucher, it’s in Fig 10 where they quote US injuries at 37.5 per 10 million km for the period 2004-2005, sourced to US Department of Transportation (2007), which is/are Traffic Safety Fact Sheets according to the footnotes. Pucher does, um, mention that injury rates comparisons across countries are particularly suspect; Figure 10 would lead on to believe the UK and US have similar fatality rates, whereas US injury rates are quoted as SEVEN TIMES higher. (Pucher’s claim/point is that NL and DK are very safe, while US and UK are very dangerous). In any event TSF does not list injury rates per unit of travel, only number of injuries, e.g. TSF 2005 quotes 45,000 injuries (these are presumably some sort of statistical estimate?). To get the rate estimates, he uses one of the surveys (household trans survey?).

Paul Schimek gathered data on the 19 cycletracks listed in table 3; he added another column “intersections per km” and sorted them into two groups, 1) Urban Side Paths and 2) Side Paths with Minimal Crossflow. And as would be predicted by traffic engineering principles, the former had very high (7.02) versus the latter which had very low (0.57) crashes per 1 Million bicycle kilometers. The published letter-the-editor of AJPH is available in full on pubmed (or draft version on google docs) which is well worth reading. He, by the way, provides an estimate for whole US bike crashes at 3.5 per 1M bike km’s; which fits rather nicely between the high/low cycletrack numbers. The bottom line is that the AASHTO guidelines (which prohibit the on-street barriers; but permit bicycle paths adjacent to the roadway where there is “minimal cross flow by motor vehicles”) , contrary to Lusk’s assertions, are well-founded. This blog post at bicycledriving.org also discusses the same AJPH article, with links to both Schimek’s published letter, and Lusk’s published response. This is wrapped up in an article the Paul wrote A Review of the Evidence on Cycle Track Safety, Paul was kind enough to send me draft copy dated October 10, 2014.

Oh, and here is John Forester’s review of Lusk’s May AJPH article. In summary, Forester says “This review does not evaluate Lusk’s method of calculating car-bike collision rates. However, the cycle tracks with high collision rates are all in high-traffic areas with high volumes of crossing and turning traffic, while the cycle tracks with low collision rates are all in areas with low volumes of turning and crossing traffic. That is what should be expected, but it says nothing about any reduction in collisions that might have been caused by the introduction of cycle tracks. The data of this study provide no evidence that cycle tracks reduce car bike collisions”.

What about Davis, CA?

The article/thesis paper Fifty Years of Bicycle Policy in Davis, CA 2007

Theodore J. Buehler has a deep history. Davis, home of course to UC Davis, installed and compared designs including what we would now call a cycle track in the late 1960’s as “experimental” designs, (emphasis added):

Lane location relative to motorized traffic

The early experiments included three different types of bike facilities (see examples at the top of this section):

- bike lanes between car lanes and the parking lane (Third St.),

- bike lanes between the parking lane and the curb (Sycamore Lane), [what we now call a cycle track, or protected bike lane] and

- bike paths adjacent to the street, between the curb and the sidewalk (Villanova Ave.).

… The on-road lanes worked best, the behind-parking lanes were the worst, and the adjacent paths were found to work in certain circumstances.

Perhaps telling, perhaps not, I have archived the .pdf referenced above as I can no longer find it on the bikedavis.us website. There is a similar version of Buehler’s paper that was published through TRB with the same title (but with a co-author, Susan Handy); its conclusions are worded somewhat differently; instead of best and worst, they just say “Eventually all lanes were converted to the now familiar configuration of the bike

lane between the moving cars and parked cars” without saying why.

Notations from the City of Davis website says (retrieved 1/19/2017. Emphasis added):

Sycamore Lane Experiment: This 1967 bike lane used concrete bumpers to separate parked cars from the bike only lane. The parked cars screened the visibility of bicyclists coming into intersections and cars would unknowingly drive into the bike lane. This bike lane design was eventually abandoned.

The 1967 separated bike lanes on Sycamore Lane didn’t prevent conflicts with turning vehicles. Today at this intersection there are special bike-only traffic signals that provide cyclists their own crossing phase. These innovative bicycle signals were the first of their kind to be installed in the United States.

Other Critiques

Ian Brett Cooper offers this critiques of a number of papers involving segregated infrastructure, e.g.:

2012 Teschke: Route Infrastructure and the Risk of Injuries to Bicyclists: A Case-Crossover Study

Selection bias: uses comparison streets instead of a before-after situation; study claims greatly increased safety on cycle tracks, but the cycle tracks chosen for the study were not representative of a typical cycle track, in that all were on roads with limited or nonexistent road intersections. It is not surprising that bicycle facilities that have little or no possibility of interaction with motor vehicles are safer than those that have many such possibilities, and if all bicycle tracks were completely separated from turning and crossing traffic, they would indeed be safer than cycling on the road. The problem is, cycle tracks with few road intersections are very rare indeed.2011 Lusk: Risk of Injury for Bicycling on Cycle Tracks Versus in the Street (Montreal, Canada)

The infamous Lusk study. Selection bias: study claims increased safety on bicycle specific infrastructure, but its street comparisons are flawed – the streets compared were in no way similar other than their general geographic location. Busy downtown streets with multiple distractions per block were twinned with bicycle tracks on quieter roads with fewer intersections and fewer distractions..

IIHS (2019) (#IIHS)

Some protected bike lanes leave cyclists vulnerable to injury

and the study page, more fully titled;

Since Washington D.C. was a primary study site, and the home of a significant amount of separated bikelanes/cycletracks, The WashPo ran a news item on the study under the title D.C.’s oldest and most popular protected bike lane has ‘highest injury risk,’ study says, two-way cycletracks being unsurprisingly the most problematic.

Highlights (part 1):* Same “case-crossover” method as Teschke et al. Bicycling in Cities Study, which is the only reliable one yet used with N. American data.* Unlike that study, there were actually PBLs installed in the cities where data was collected.* They found NO safety benefit for one-way PBLs and a significant indication of higher risk with two-way PBLs.* They reproduced the Teschke finding of higher risk for going downhill and VERY high risk due to streetcar tracks (all in Portland, OR).Highlights, part 2:* Only 40% of bicyclist injuries were due to moving motor vehicles (data are from emergency department visits).* 12% of injuries were due to non-moving motor vehicles. These include dooring, but it is not presented separately. The figure rises to 20% of injuries on “major-roads.” They do not separate roads with and without on-street parking.* Ordinary bike lanes appear to reduce risk BUT the presence or lack of on-street parking may be a confounding factor. The risk reduction is only AWAY from intersections. At intersections there was a 4-fold increase in risk (but not enough data to be statistically significant).* Further, there was no evidence that bike lanes reduce the risk of collision with moving motor vehicles (see Table 6).* There were only 18 injuries on one-way PBLs, which was not enough to determine how they affect risk EXCEPT that there was enough to say that they increase the risk of bike-ped injuries.* Even with only 21 injuries on two-way PBLs, there was enough evidence to show that they increase risk by an order of magnitude, specifically collisions with bicyclists and pedestrians (Table 6).The study is yet more evidence that looking at motor vehicle crash statistics (which ignore incidents not involving mvs) will not give a true picture of the safety effects of bike facilities.

.

Why cities with high bicycling rates are safer for all road users

Another Marshall and Ferenchak study Why cities with high bicycling rates are safer for all road users; was commented on in this letter by Paul Schimek. In the study, F&M claim safety-in-numbers was not shown, but that “Better safety outcomes are instead associated with a greater prevalence of bike facilities – particularly protected and separated bike facilities”. Schimek observse that they mixed “trails” (off-street paths removed from roadways) with true protected and separated bike facilities. He also points out “Third, a significant p-value does not imply a causal relationship. With 112,918 observations, it is not difficult to find coefficients that pass conventional significance tests”. (is that “p-hacking“?). As well as some other observations.

An earlier F&M paper originally titled The Relative (In)Effectiveness of Bicycle Sharrows on Ridership and Safety Outcomes seems to have used the same dense statistical techniques they say establishes their premise; it involves census tract block groups.

.

48th Street; Piedmont to Guadalupe gets SLMs (sharrows)

It involves the odd geographic position of the Ahwatukee area of Phoenix; and the the almost complete lack of connectivity for Ahwatukee residents to anywhere else, (Tempe, Chandler, and indeed the main portion of Phoenix) except by car-choked umteen lane roads.

Ahwatukee is called — sometimes derisively, sometimes happily — the world’s largest cul-de-sac. Setting aside 48th street for a moment; Ahwatukee’s ONLY ingress/egress is Pecos Rd (which is loop 202, a limited-access highway), Chandler Blvd (10 lanes?), Ray Road (10 lanes), Warner Road (only 6 lanes?), Elliot Road (10 lanes?). So these are all either a limited-access freeway, or humongous monstrosities that have interchanges with I-10.

In short, these are all car-choked, car-sewers. They are not particularly bad for cyclists; two (Ray, and Chandler) have wide-curb lanes; Warner has nice narrow lanes; I find Elliot road to be most annoying as it is “critical width“; that is to say not wide yet not narrow enough to be perceived as too narrow to share by many motorists. Yet many cyclists, understandably, don’t want to do it. It is a thoroughly obnoxious experience for pedestrians, too. Continue reading “48th Street; Piedmont to Guadalupe gets SLMs (sharrows)”